Supreme Court victory for Bobby Moore

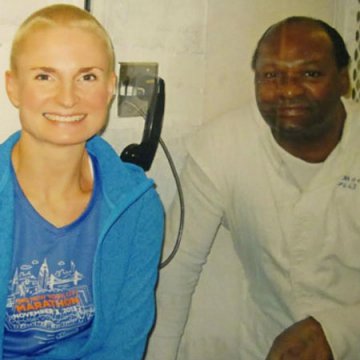

Kimmie Fearnside, Associate Solicitor, writes on a case that is close to our heart

In a 5-3 majority decision, the Supreme Court (the Court) has determined that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA)’s application of the outdated medical diagnostic standard in Bobby Moore’s case, including particular nonclinical factors, did not comport with the Court’s jurisprudence and was not in accordance with the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishments.

Mr. Moore’s case has endured a complex procedural history. He was convicted of capital murder in 1980 at the age of 20, a sentence that was later vacated by a federal habeas court in 1995 (and affirmed by the Fifth Circuit) on the basis of ineffective assistance of counsel. In 2001, Mr. Moore was resentenced to death, which was affirmed on appeal. At a further habeas court hearing in 2014 Mr. Moore pursued a fresh claim for intellectual disability, following the Court’s decision in Atkins v. Virginia in 2002. Consulting the current medical diagnostic standards, in particular relying on the 11th edition of the American Association on Intellectual Developmental Disabilities clinical manual (AAIDD-11) and the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-V), the habeas court was satisfied that Mr. Moore had established on the basis of the three core elements ((i) intellectual functioning deficits; (ii) adaptive deficits; and (iii) onset whilst a minor) that he was intellectually disabled. On appeal, the CCA held that the habeas court had erred by “using the most current position, as espoused by AAIDD, regarding the diagnosis of intellectual disability rather than the test… in Briseno.” In the CCA’s 2004 decision in Ex Parte Briseno , in the absence of appropriate legislation enacting the mandate in Atkins, it chose to adopt the older 1992 version of DSM-IV, and introduced various nonclinical evidentiary standards into the assessment of whether the adaptive deficits were “related” to the intellectual functioning deficits.

On a petition for certiorari, the Court was invited to determine whether the CCA’s decision to prohibit the use of current medical standards on intellectual disability, and require the use of outdated medical standards violated the Eighth Amendment and the Court’s decisions in Hall v. Florida and Atkins v. Virginia in determining whether an individual may be executed. The opinion of the Court, handed down on 28 March 2017, was delivered by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg (with whom Justices Kennedy, Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan concurred). In light of the sentiments expressed at the oral hearing in November last year, the Court’s decision is not wholly surprising but nevertheless a definite relief for Mr. Moore. The Court reiterated that adjudications of intellectual disability for the purpose of capital cases should be “informed by the views of medical experts”, as these inevitably reflected “improved understanding over time”. Whilst Atkins and Hall had allowed States discretion in enforcing the restriction on the execution of intellectually disabled individuals, this discretion was not unfettered and must always be “informed by the medical community’s diagnostic framework”. In Hall, the Court had determined that Florida had violated the Eighth Amendment by disregarding “established medical practice”. Where an IQ score falls within the clinically established range, as Mr. Moore’s - falling between 69 and 79 - did, Hall mandates that the enquiry must go on to consider other evidence of intellectual disability. CCA failed to do so. The CCA also incorrectly overemphasised Mr Moore’s adaptive strengths, and in adopting the nonclinical Briseno factors, failed to properly consider his adaptive deficits.

Indeed, on this latter point the Court was unanimous in confirming that such factors were an unacceptable method of enforcing the mandate in Atkins. The Court confirmed that such factors are an “outlier” in comparison to other States, and even within Texas’ own practice outside of the death penalty context. The dissenting opinion (filed by Chief Justice Roberts, in which Justices Thomas and Alito joined) otherwise substantially departed from the majority view. On the factual enquiry, the dissent disagreed on the appropriate assessment of Mr. Moore’s IQ score, and considered that on the evidence, a further assessment of intellectual disability would not have been required in any event. Broader, however, was their concern for the precedential implications of elevating medical assessment of clinical practice in the context of judicial decision making. Justice Roberts expressed concern about disagreement even amongst the medical community as to the accepted standard of diagnosis, noting that clinical guides “do not seek to dictate who is morally culpable”. Rather, “judges, not clinicians, should determine the content of the Eighth Amendment”.

The contention that Hall has now been unhelpfully expanded is, respectfully, exaggerated – if anything, the common sense decision in Moore is a natural clarification of the law and provides welcome certainty to individuals suffering from intellectual disability. For States to continue to apply guidelines superseded by advances accepted in the medical community is plainly untenable and leads to inconsistent and unsafe decisions country-wide. It is encouraging that the Court (especially then at eight members) appears willing in the death penalty context to scrutinise and uphold procedural protections, as in Moore, or to indirectly strike down clearly prejudicial practices, as in Buck v. Davis.

After 37 years of fighting on death row, Mr. Moore will now see his case be remanded for further proceedings in the Texas trials courts (and ultimately the CCA) where it is hoped that, in light of the Court's decision, the death penalty will be considered inappropriate.

This article is by Kimmie Fearnside. To see Kimmie's full article (including references), click here.